Image Processing in a Web Worker

WebRTC (Real-Time Communication) has many great uses, much of which is still relatively untapped. One of my favorite side effects of WebRTC arriving in browsers is the ability to put a live web camera feed into a video element. Once those two are paired, you can start performing real-time image processing on the content via a canvas element and the ImageData object.

What Performance

Analysis of a web camera stream can be very demanding on the browser ...

Consider a single image from a web camera stream that is 640x480 pixels - relatively small by modern standards. That is 307,200 pixels. The first step in many image processing algorithms is to remove color (noise) from an image by making it grayscale. This means a loop with 307,200 iterations before we can really start analyzing the image content.

The next step in image processing is often to perform a softening of the image detail through a Gaussian blur (more denoising). A Gaussian blur represents O(kernel * width * height). This means that applying a blur on the above image (640x480), with a kernel of three (3) yields 921,600 operations. That is on top of the 307,200 we needed to move from color to gray.

If we approach this work in a requestAnimationFrame() callback, then we are going to crush rendering performance. If we approach this work in a setTimeout() callback, we will crush the event loop. Either way, we are going to make the page unresponsive to user interaction. Ideally, we need a way to offload this work to another thread.

Enter Web Workers

Web Workers give us a separate thread for working with data, but they come with a trade-off - no access to the DOM. In the case of image processing however, this does not matter. Image processing involves running a lot of maths on a specific set of data. The end result is generally a geometric description of the content (lines, boxes, etc). This makes image processing with Web Workers a perfect fit.

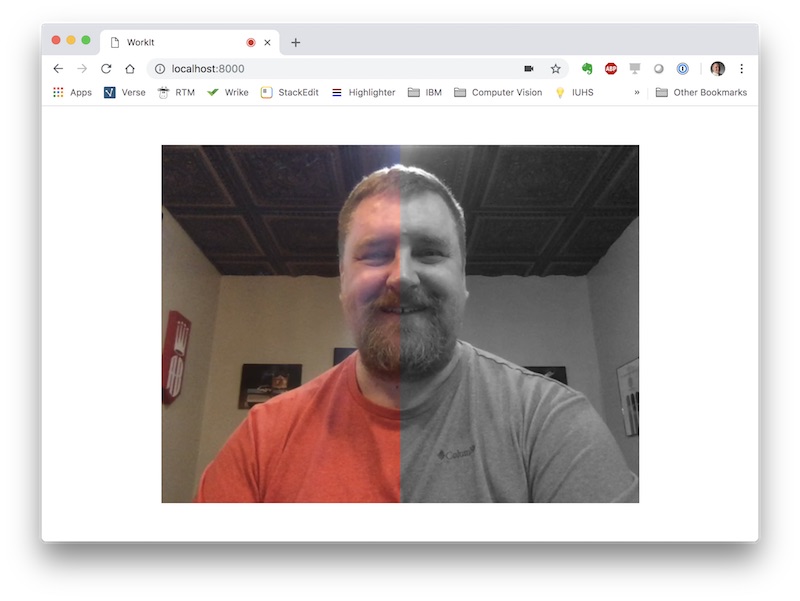

In this example, we will take frames from the video element via canvas, get an ImageData object representing half of the frame, process that frame to grayscale in a Web Worker, and then display the results over the video.

A Tale of Two Threads

To process a frame of the video, we will need to place it onto a canvas element. This is what will allow us to get the ImageData for processing. To show the frame, we can overlay a canvas on the video, where the canvas will be otherwise transparent unless we paint something on it. This then is actually two separate threads. One for the processing and one for the rendering.

When it comes to rendering, that is the realm of requestAnimationFrame(). This will help us to stay in sync with the browser refresh and optimize painting operations. We should generally strive to keep the requestAnimationFrame() callback aligned with rendering only. We do not want to capture frames of the video, or process the frame to grayscale. If there are grayscale results, we want to render them, but we do not want requestAnimationFrame() beholden to the processing itself.

When it comes to the processing, we can grab a frame of the video, and put it on a canvas, without impacting the rendering cycle. The processing to gray scale will happen in a separate thread, so that will not impact rendering either. Then when we have the resulting grayscale bytes we need to render them, but we do not want to tie the two together. We want to offload the resulting ImageData, and move on to processing the next frame.

What does all this mean? It means that we need a shared property that the requestAnimationFrame() and worker results can access. Whew! We will come back to this concept in a moment, but for now, all that boils down to:

class WorkIt {

constructor() {

this.grayscale = null;

}

}Decoupling two parts of an application is a powerful technique I have also used successfully in IoT.

Setup the Web Worker

Declaring a Web Worker is easy enough, but we will want to make sure the scope is at a place where we can refer to the instance throughout our class. To get data from the main thread over to the worker, we call Worker.postMessage(). On the worker side, we will implement an event listener for the message being posted. Likewise, when the worker is finished, it will call Worker.postMessage() to send data back to the main thread. Then to handle it, we need to add a listener for the message being posted.

class WorkIt {

constructor() {

this.grayscale = null;

this.worker = new Worker( 'grayscale.js' );

this.worker.addEventListener( 'message', ( evt ) => this.doWorkerMessage( evt ) );

}

}There are some constraints on the data that can be passed. Namely that the object needs to conform to the structured clone algorithm. Most built-in data types, including

ImageData, conform to this algorithm.

Canvas the Neighborhood

As previously mentioned, we will need two canvas elements. One which gets a full frame from the video, and one which renders the resulting grayscale image. This means two canvas element references, and two context instances. In the interest of convenience, I like to bundle these two together in a custom class. This keeps my code cleaner.

class ImageCanvas {

constructor( path ) {

this.canvas = document.querySelector( path );

this.context = this.canvas.getContext( '2d' );

}

}

class WorkIt {

constructor() {

this.grayscale = null;

this.worker = new Worker( 'grayscale.js' );

this.worker.addEventListener( 'message', ( evt ) => this.doWorkerMessage( evt ) );

this.input = new ImageCanvas( '#input' );

this.output = new ImageCanvas( '#output' );

}

}I See You

Now for some video. Once the stream loads, you will notice a call to two different methods. These are the method calls that kick off our rendering and processing hooks. As we will see in a moment, the draw() method will invoke requestAnimationFrame() and assign itself as the callback. This effectively sets up the rendering loop inline with the actual rendering process of the browser. The process() method will capture the frame and post it as a message over to the worker. When the work finishes, we will land back in the main thread. More on that in a moment.

this.video = document.querySelector( 'video' );

navigator.mediaDevices.getUserMedia({video: true, audio: false} )

.then( ( stream ) => {

this.video.srcObject = stream;

this.video.play();

this.draw();

this.process();

} )

.catch( ( err ) => {

console.log( err );

} );Draw the Frame

The draw() method contains very little code, and that is by design. We could grab the frame, process it, and overlay it on the video all in the draw() method. That would work. The problem is that all those operations would need to happen before the browser rendered anything. With enough processing, this will bring our frame rate down to close to the single digits.

draw() {

if( this.grayscale !== null ) {

this.output.context.putImageData(

this.grayscale,

this.output.canvas.clientWidth / 2,

0

);

}

requestAnimationFrame( () => {return this.draw();} );

}What we will do instead is look for that touch point between rendering and processing, which in this case is the grayscale property. If an ImageData value is in the grayscale property, it will be rendered on the next pass. And that is it. Again, try and keep the activities in requestAnimationFrame() oriented around the things that actually need to be rendered.

At this point, the rendering is happily going about its work. Likely at around a nice, buttery smooth, 60 frames per second. It is just sitting there, waiting for something to render. Now let us give it something to render.

Capture the Frame

The process() method is also pretty slender - three whole lines. First we draw the currently displayed video frame to an offscreen canvas. Next we get an ImageData object representing the right portion of that frame. Then we send the ImageData over to the worker via Worker.postMessage().

process() {

this.input.context.drawImage( this.video, 0, 0 );

const pixels = this.input.context.getImageData(

this.input.canvas.clientWidth / 2,

0,

this.input.canvas.clientWidth / 2,

this.input.canvas.clientHeight

);

this.worker.postMessage( pixels );

}As it turns out, moving 307,200 values around in memory to construct the

ImageDataobject still takes some time. In fact, it will be the most significant part of the work on the main thread in this case. What would be nice is something likeImageDatathat is optimized for rendering. It turns out that the[ImageBitmap](https://caniuse.com/#feat=createimagebitmap)object is that class, but it also turns out thatImageBitmapis not broadly implemented in browser yet (October 2018).

Get to Worker

Turning an image from color to grayscale can be accomplished in a few different ways - some more scientific than others. My preferred method for image processing is to average the red, green, and blue channels. Then you place that resulting average value back into the red, green, and blue channels. This is where we make those 307,200 iterations. It is detached from the rendering thread and callback event loop.

self.addEventListener( 'message', ( evt ) => {

let pixels = evt.data;

for( let x = 0; x < pixels.data.length; x += 4 ) {

let average = (

pixels.data[x] +

pixels.data[x + 1] +

pixels.data[x + 2]

) / 3;

pixels.data[x] = average;

pixels.data[x + 1] = average;

pixels.data[x + 2] = average;

}

self.postMessage( pixels );

} );With the averaging of the pixels complete (a.k.a. grayscale), we call Worker.postMessage() to send the result back to the main thread. Imagine a Gaussian blur happening here. Edge detection. Polygon extraction (object detection). All happening away from the rendering.

And We Are Done

Back in the main thread, our message callback gets, um, called back. Here we offload the processed ImageData object off to the grayscale property. After that, we call process() again to do the same to whatever frame is being displayed by the camera stream (on the video element) at the moment.

doWorkerMessage( evt ) {

this.grayscale = evt.data;

this.process();

}You might be asking how the ImageData object gets rendered. Well, now that there is an ImageData object to render, the next time the requestAnimationFrame() handler is called, it will see that object and paint it onto the canvas that overlaid on the video.

The Results Are In

If we start looking at the performance in detail, we will see that rendering stays around 60 fps. It does dip from time to time (to around 40 fps on my machine), and if we look at the operations taking the most time, what we will discover is that it has to do with getting the ImageData from the main thread over to the worker. That 307,200 element array inside the ImageData object is pretty beefy no matter how we feel about it.

As it turns out, the browser vendors noticed this as well, and there is an approach we can use to cut that time almost in half. I will cover that in the next installment of this series.